by | | Antique / Vintage Toys -Marx - Tonka - Fisher Price - Hubley -Wyandotte-

We have several dealers who specializes in antique toys. We always have new inventory coming in. Right now we have approximately 10 of the shooting gallery toys the graphics on them are in excellent condition. Decorators are using them in kids rooms as pictures and decoration.

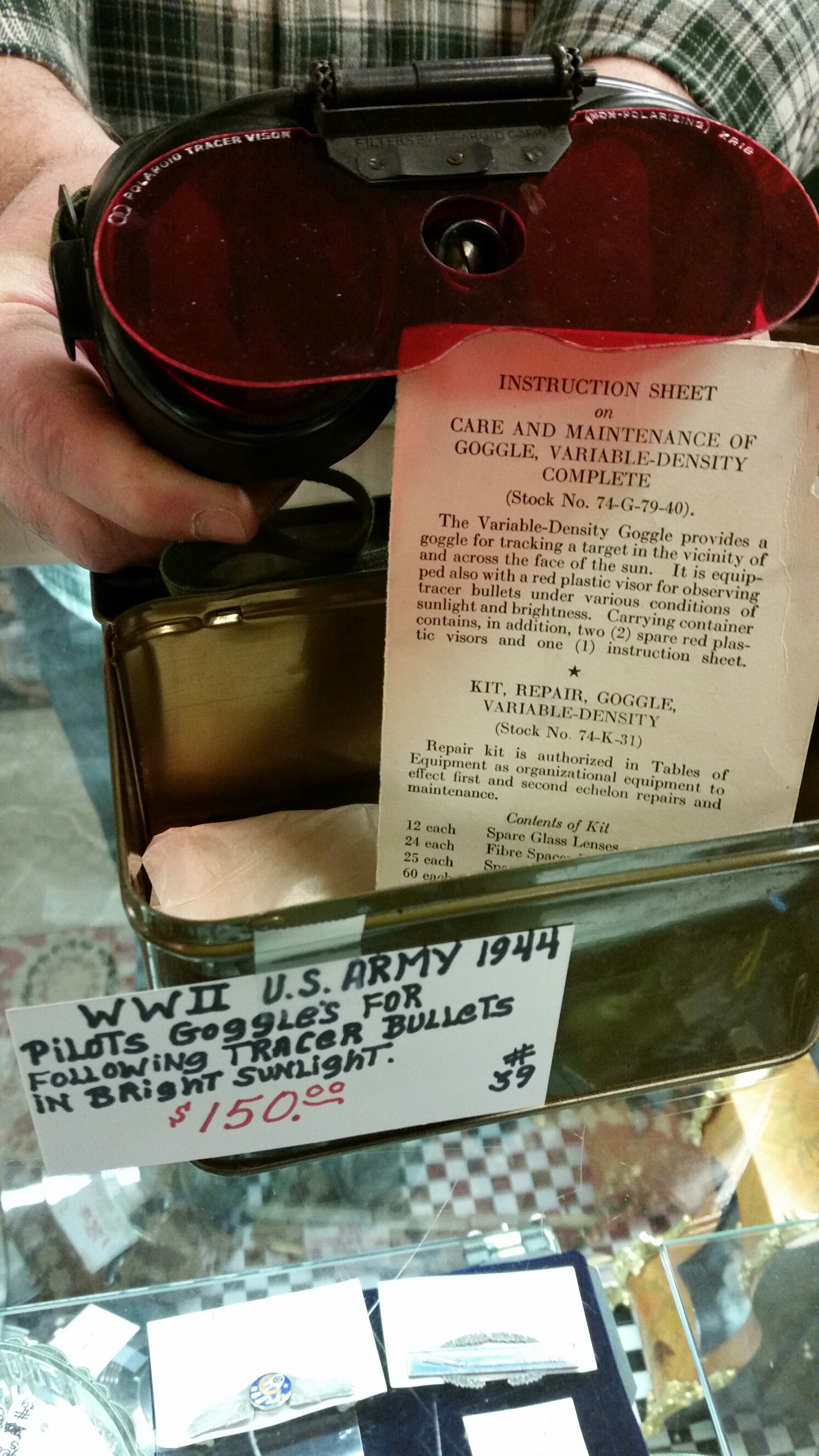

by | | Antique / Vintage Military - WWI - WWII - Korean War- Vietnam War - Civil War - And More

We have a dealer who has a expansive collection of all ages and of different countries of Military items. You need to come in and see all of the different items that he has.

The need to protect the head in battle has inspired a range of solutions over the last 2,000 years, some wildly impractical, others elegantly utilitarian. Metal helmets were a part of traditional European armor as early as 400 BC, when Roman Montefortino-style helmets were introduced. These heavy headpieces came in various shapes, from a pointed, conical design topped with a plume to the more familiar “kettle hat” shape with a rounded dome and wide circular brim.

Some early helmets covered the entire head and neck, and many included a frontal grill or hole-punched faceguard for greater protection. The goal of this equipment was protection, but beauty was not sacrificed in the process. For example, by the 1st century, ornate headgear created for higher-ranking officers was often engraved with intricate floral designs or decorations resembling human hair. Helmet styles reached their peak of complexity in France during the 1800s, when the headgear for Napoleon’s armies incorporated fur, feathers, and gilt trimming.

Possibly the most distinctive military headwear is the famous Pickelhaube, designed for the Imperial German Army. First introduced in 1842, the Pickelhaube features a large gold eagle emblem above its visor and is topped with a threatening gold spike. Variations on this style were produced through World War I, some incorporating leather chinstraps or marked with specific unit decorations. The German helmet was quickly imitated by other militaries, as seen in the design of French and British headgear from the late 1800s.

During the same era, the medieval kettle hat form was adapted for the safari helmet style. Originally made from pith, a lightweight material derived from an Indian swamp plant, safari helmets were primarily used by European militaries on patrol in tropical colonies. The style was popularized after British troops wore pith helmets during various conflicts in colonial India during the 19th century.

Though headpieces grew more sensible during the 20th century, metal still provided the best protection against head injuries. The dark grey, blue, or green helmets of World War I were mostly made from steel, which was easily mass-produced. These examples include the French Adrian helmet, with its small metal comb along the top, and the German M16, whose design was prompted by a campaign from the medical community for improved head-protection.

World War II helmet styles were even simpler, mostly consisting of plain metal domes made to fit any head size. Some armies marked their helmets with painted insignia, like the infamous German swastika or SS logos, while a few continued to use more detailed brass emblems, as seen on the headgear of Spain, Holland, and Switzerland. The most common look was typified by the American M1, or “steel pot” design, which was made from a single metal sheet with a gently sloping rim. The olive-green M1 included an adjustable plastic liner and was equipped with two metal loops for a chinstrap. The M1 style was used through 1985, with the addition of camouflage canvas coverings during the Vietnam War.

Increased use of air forces in World War II also meant a proliferation in flight helmet designs. These varied from the gigantic German crash helmets, complete with protective lea…

by | | Ironstone - English - French -Transferware, Uncategorized

A great collection English transferware in brown and blue. Highly collectible Kama getting harder and harder to find. A wide variety of butter pat’s in Ironstone and also in transferware.Ironstone china is not porcelain; it is a porous, glaze-covered earthenware, consisting of clay mixed with iron slag and feldspar, and a small amount of cobalt. First patented in 1813 by Charles James Mason in Staffordshire, England, it was decorated with under-glaze transfer patterns. Eventually, by the 1840’s, undecorated, or white ironstone china, was being manufactured for export to the Americas. This is the white ironstone china collected today. Older white ironstone has an almost bluish cast to it, due to the cobalt, while later examples have a creamy color.Transferware is pottery. It can be earthenware or porcelain, ironstone or bone china. It’s most distinctive feature is a pattern that has been applied by transferring an etching onto the pottery. This is done by inking an etching which has been engraved on a copper plate, applying a specially sized paper to the copper plate, and transferring the pattern left on the inked paper onto an undecorated piece of pottery. The pottery is then dipped in water to float off the paper, glazed, and re-fired.

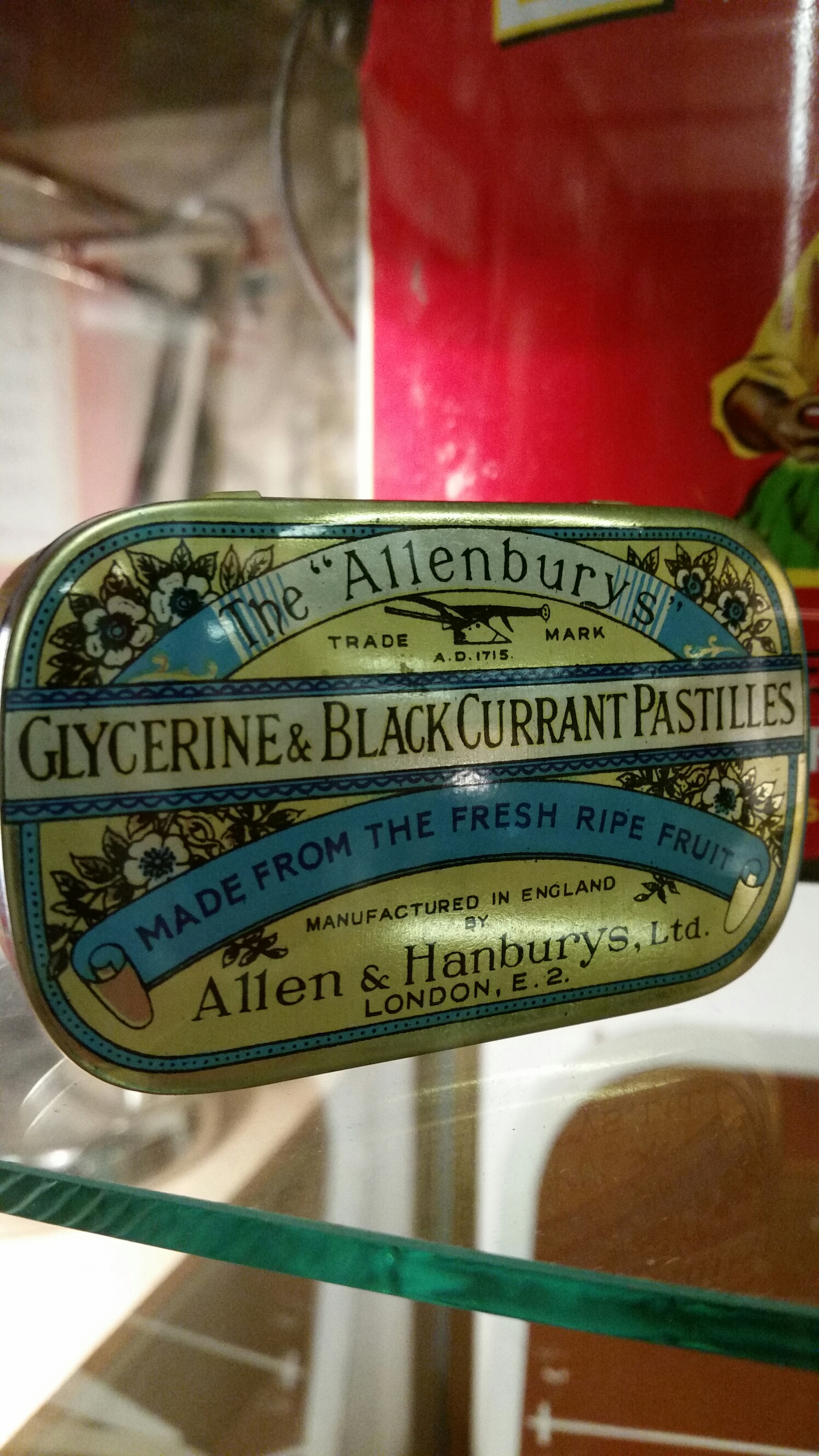

by | | Antique Tins - Coffee - Marshmallow - Tabacco - Oil -Pharmaceutical - Spice -Lard - Chip- Peanut Butter - Oyster

We have an incredible selection of antique and vintage tins. They are highly collectible item. They are being featured in all the decorator magazines, websites and TV shows.

by | | Vintage / Antique Signs

Antique and vintage signs are highly sought after by collectors for their beauty, enduring historic value, and because they make great discussion pieces. Used to advertise everything from soda to farm equipment to household appliances, key genres include wood, porcelain (aka enamel), tin, and neon.

Porcelain enamel signs were first produced in Europe in the late 1800s, and became popular in the U.S. in the 1890s. Porcelain signs were made of powdered glass fused onto rolled iron. Different colors were stenciled on and fired, creating a different layer for each color; although later porcelain signs were silkscreened. Porcelain signs were durable and able to withstand exposure to the elements, so tens of thousands were made. But during the World War II scrap drives, many were melted down. Eventually high labor costs caused porcelain signs to fall out of favor in the 1950s.

Tin signs were also melted in WWII scrap drives, halting production almost permanently. Although some tin signs were made after the war, their reemergence was short lived. Tin signs reached their peak of popularity in the 1920s and were usually painted, screenprinted, or stamped. But they were not as durable as porcelain signs, and were prone to rust.

The first neon sign was introduced in 1912, for a Parisian barber. Neon signs contain tubes filled with neon or inert gasses that glow when a high voltage is applied. Though popular in the 1920s and 1930s, they were expensive to make and very fragile. In the 1940s and ’50s, custom-made neon signs were produced in small quantities for businesses like restaurants, clubs, bars, hotels, and auto dealerships. More modern mass-produced neon signs for companies like Budweiser and Coca-Cola can also be collectible.

Some collectors also seek out vintage cardboard signs, which were popular in the mid-20th century and were used to advertise a broad range of consumer items (soda, beer, candy, etc.) and upcoming events, like the circus. Other sign formats, like and door pushes and pulls, are highly sought after as well.